Títle: Homage to Catalonia

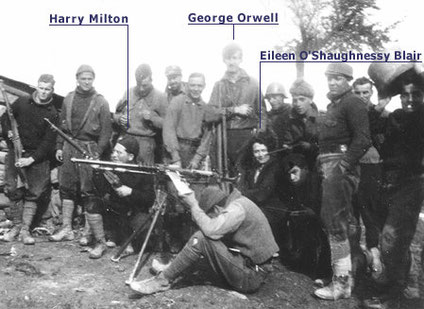

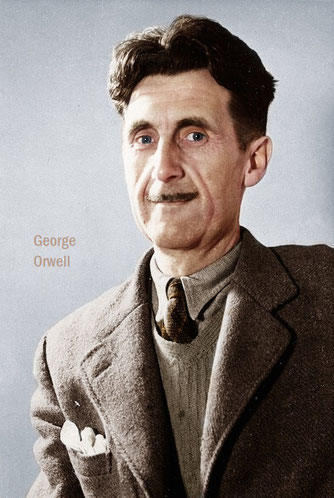

Author: George Orwell (Eric Blair)

Publisher: Penguin Books Ltd

Publication date: 2013 (1938)

Sinopsis: Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic Socialism as I understand it'. Thus wrote Orwell following his experiences as a militiaman in the Spanish Civil War, chronicled in Homage to Catalonia. Here he brings to bear all the force of his humanity, passion and clarity, describing with bitter intensity the bright hopes and cynical betrayals of that chaotic episode: the revolutionary euphoria of Barcelona, the courage of ordinary Spanish men and women he fought alongside, the terror and confusion of the front, his near-fatal bullet wound and the vicious treachery of his supposed allies.

A firsthand account of the brutal conditions of the Spanish Civil War, George Orwell's Homage to Catalonia includes an introduction by Julian Symons in Penguin Modern Classics.

book review

Where shall I start talking about today's book? Perhaps the most curious thing would be to say that the first time I heard about it I was in a small village in England, and that an English friend of mine convinced me to read it.

What would you think if I told you that the famous author Eric Blair -better known as George Orwell- not only came to Barcelona during the Spanish Civil War to fight against fascism, but also wrote a book describing his experiences? Experiences that would later inspire him to write "1984". And what's more... what would you say if the title of this book on the 1936 war wasn’t called something like to "Memoirs of the Spanish Civil War", but actually none other than... "Homage to Catalonia"?????!? Ho-mage to Ca-ta-lo-nia. Amazing.

And of course, you surely/probably think that reading a book about war memories has to be boring, and exclusively interesting for those who love history... But of all the words that come to my mind to describe this book surely there is one that you wouldn't guess in a thousand years... Shall I tell you? This word is... Funny.

It is not the only one, though. It would come along with adjectives such as: heart-breaking, exciting, irreverent and thrilling. Orwell shows us the two faces of the war, from the initial exaltation to the pantomime of the trenches.

p.16 “Many of the troops opposite us on this part of the line were not Fascists at all, merely wretched conscripts who had benn doing their military service at the time when war broke out and were only too anxious to escape. Occasionally small batches of them took the risk of slipping across to our lines. No doubt more would have done so if their relatives had not been in Fascists territory. It struck me that they were indistinguishable from ourselves, except that they wore khaki overalls."

But yes, I have to admit that whilst reading I couldn't help but let out some incredulous laughter. Orwell uses irony to relate some of the toughest facts, and doesn't mince his words when it comes to saying what he thinks at all times. I must say he "spares no one" and is the first to charge against his own people.

p.11 «Some of the journalists and other foreigners who travelled in Spain during the war have declared that in secret the Spaniards were bitterly jealous of foreign aid. All I can say is that I never observed anything of the kind. I remember that a few days before I left the barracks a group of men returned on leave from the front. [...] The French were very brave, they said; adding enthusiastically: 'Más valientes que nosotros' - 'Braver than we are"' Of course I demurred, whereupon they explained that the French knew more of the art of war - were more expert with bombs, machine-guns, and so forth. Yet the remark was significant. An Englishman would cut his hand off sooner than say a thing like that.»

The style is more agile than I imagined, and some of the anecdotes he explains have helped me to ratify others that I had already heard, but many have left me open-mouthed.

p.128 «'Run!' I yelled to Moyle, and jumped to my feet. And heavens, how I ran! I had thought earlier in the night that you can't run when you are sodden from head to foot and weighted down with a rifle and cartridges; I learned now you can always run when you think you have fifty or a hundred armed men after you.»

p.133 «When we went on leave I had been a hundred and fifteen days in the line, and at the time this period seemed to me to have been one of the most futile of my whole life. I had joined the militia in order to fight against Fascism, and as yet I had scarcely fought at all, had merely existed as a sort of passive object, doing nothing in return for my rations except to suffer from cold and lack of sleep. Perhaps that is the fate of most soldiers in most wars. But now that I can see this period in perspective I do not altogether regret it. [...] They formed a kind of interregnum in my life, quite different from anything that had gone before and perhaps from anything that is to come, and they taught me things that I could not have learned in any other way.»

p.88 «For the Spanish militias, while they lasted, were a sort of microcosm of a classless society. In that community where no one was on the make, where there was a shortage of everything but no privilege and no book-licking, one got, perhaps, a crude forecast of what the opening stages of Socialism might be like. And, after all, instead of disillusioning me it deeply attracted me.»

"And where is the homage to Catalonia?" you might be asking yourselves. I must admit that poor George does not start out very well, because the first time he was put a "porró" (a traditional pitcher) before him, he refused to drink because it reminded him of a hospital chamber pot. Do not judge him, because he spent a good part of his life being ill. Oh! And when he saw the "Sagrada Família" facade for the first time he wished it had been bombarded, because he said it was "one of the ugliest buildings in the world." Now, don't grab the torches yet... We must remember that in the thirties it wasn't that stunning...

What really impressed Orwell was the revolutionary spirit he observed when he arrived in the capital.

p.4 «Down the Ramblas, the wide central artery of the town where crowds of people streamed constantly to and fro, the loudspeakers were bellowing revolutionary songs all day and far into the night. And it was the aspect of the crowds that was the queerest thing of all. In outwards appearance it was a town in which the wealthy classes had practically ceased to exist. Except for a small number of women and foreigners there were no 'well-dressed' people at all. Practically everyone wore rough working-class clothes, or blue overalls or some variant of the militia uniform. All this was queer and moving.»

p.11 “[...] I would sooner be a foreigner in Spain than in most countries. How easy it is to make friends in Spain! Within a day of two there was a score of militiamen who called me by my Christian name, showed me the ropes and overwhelmed me with hospitality. I am not writing a book of propaganda and I do not want to idealze the POUM militia. [...] But...

...I defy anyone to be thrown as I was among the Spanish working class -I ought perhaps to say the Catalan working class, for apart from a few Aragonese and Andalusians I mixed only with Catalans- and not be struck by their essential decency; above all, their straightforwardness and generosity.»

This is a message that Orwell repeats throughout the book, that the Catalan working class truly impressed him. The truth is that I would quote him forever, because the tales about his experiences are fascinating. Even the appendices you'll find at the end of the book are much more interesting, funny, and clairvoyant than you can imagine. There he talks about party politics and press manipulation.

p. 260 «As for the kaleidoscope of political parties and trade unions, with their tiresome names -PSUC, POUM, FAI, CNT, UGT, JCI, JSU, AIT- they merely exasperated me. It looked at first sight as though Spain were suffering from a plague of initials.»

At first Orwell confesses that he didn't understand there were serious differences among these political parties, but he later witnessed the complex plot of enmity and treason between them.

In addition, after everything he went through he seriously questioned the truthfulness of the media:

p.201 «The thing that had happened in Spain was, in fact, not merely a civil war, but the beginning of a revolution. It is this fact that the anti-Fascist press outside Spain has made it its special business to obscure. The issue has been narrowed down to 'Fasciscm versus democracy' and the revolutionary aspect concealed as much as possible. In England, where the Press is more centralized and the public more easily deceived than elsewhere, only two versions of the Spanish was have had any publicity to speak of: the Right-wing version of Christian patriots versus Bolshviks dripping with blood, and the Left-wing versions of gentlemanly republicans quelling a military revolt. The central isuue has been successfully covered up.»

On the other hand, when he found himself in the midst of the May Days of 1937 in Barcelona, he could not understand how newspapers wrote more and more contradictory and manipulative accounts. In the second appendix he speaks in detail and shows fragments of the articles in question:

p.312 «There is nothing like starting off with a reversal of roles. The local Assault Wards attack a building held by the CNT, so the CNT are represented as attacking their own building – attacking themselves, in fact. [...] It would be difficult to pack together more contradictions than are contained in these few short passages. At one moment the CNT are attacking the Telephone Exchange, the next they are being attacked there; a leaflet appears before the seizure of the Telephone Exchange and is the cause of it, or alternatively, appears afterwards and is the result of it; the people in the Telephone Exchange are alternatively CNT members and PUUM members – and so on. And in a still later issue of the Daily Worker (3 Jund) Mr J. R. Campbell informs us that the Government only seized the Telephone Exchange because the barricades were already erected!”

As I previously mentioned, it is clear that all this inspired him to write one of his best known novels ("1984"), where the Ministry of Truth rewrites the history through the media.

And I wonder... How can this book not be even half as famous in Catalonia as it is in England? We need to change this by all means! So read it... read it and spread the word.

Even though Orwell didn't die in combat, the aftermath of his wounds and his stay in the trenches during the Spanish Civil War accompanied him for the rest of his life, and he died of tuberculosis in 1950. So what better way to pay homage to him than reading his work?

Mx

Write a comment